Born

into a modest Gujarati family, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

was

the fifth child of Karamchand and Putliba. He was born on October 2, 1869,

in Porbandar, where his father was Dewan. As the youngest child, he was

mischievous. As a youth, he was an average student who was very shy and

unable to speak. He says he ran home from school to avoid befriending and

talking to other students |

|

During

his childhood, Mohan became a victim of peer pressure. He experimented

with smoking with his older brother. Both would collect the stubs after

their uncle had extinguished his cigarette, remove the tobacco from them

and roll a cigarettes for themselves. This did not last long because Mohan

found it discomforting and distasteful. Then he experimented with meat-eating

with a Muslim friend who convinced Mohan that the only reason why the English

were so tall and powerful and able to rule over India was because they

ate meat. Unless Indians became meat-eaters, India would never become free

was his argument. For almost a year, meat-eating became a clandestine affair

which entailed lies, deception and even stealing. He had to find the money

to pay for the food-which meant stealing from home; he had to make excuses

for not eating at home-which meant lying and deception. Soon, this became

intolerable, and Mohan made a confession to his father.

|

|

Karamchand

was unwell and, therefore, resting in bed. Mohan did not have the courage

to tell him about his clandestine escapades, so he wrote a confession and

handed it over to his father to read. Tears welled up in his father's eyes;

he embraced Mohan, and both of them cried. Mohan writes in his autobiography

that it felt as though their tears washed away the sin of deception that

he had committed. He decided never again to indulge in such acts.

Mohan

was married at the age of 13, since child marriages were prevalent then.

His bride was Kastur, the daughter of Gokuldas Makanji, the Mayor of Porbandar.

She was also 13 years old, and she taught Mohan his first lesson in non-violence.

Mohan had no idea what the role of a husband should be, so he bought some

pamphlets, which were written by male chauvinists and suggested that an

Indian husband must lay down the rules for the wife to follow. Thus, Mohan

laid down the first rule when he told Kastur,

"Henceforth,

you will not go out of this house without my permission."

Kastur

heard him quietly. She did not retort or say anything. A few days later,

Mohan realized that she still flouted his rule and went out of the house

to the temple and to the market and sometimes visiting friends and relatives.

He confronted her that evening.

"How

dare you disobey my orders?" he barked at her.

Once

again, very calmly and without loosing her cool, Kastur asked: "Who is

senior in this house? Are you superior to your mother? Should I tell her

that I will not go out with her until you give me permission? If that is

what you want let me know." She was so calm and collected that Gandhi had

no answer. He never questioned her again. It is a lesson for all of us

to learn. When we face such situations we retort and react angrily making

the situation worse and sometimes leading to the breaking of the relationship.

But calmly, with common sense, one can achieve the same results.

In May 1883, at the age

of 13, Gandhi was married through his parents' arrangements to Kasturba

Makhanji (also spelled "Kasturbai" or known as "Ba"). They had four sons:

Harilal

Gandhi..., born in 1888; Manilal Gandhi..., born

in 1892; Ramdas Gandhi..., born in 1897; and

Devdas

Gandhi..., born in 1900.

Harilal Mohandas Gandhi

(1888- 18th June 1948) was the first son of Mahatma Gandhi. Mahatma would

not allow his son to study law as a show of rebellion against a Western

education and Harilal eventually grew weary of this, and rebelled.

Harilal converted to Islam and adopted the name "Abdullah Gandhi", but

later again converted to Hinduism. In Early years Harilal helped his father

in revolution against British Government for their attitude about racism.

He had always wanted to go for higher studies and wanted to become a barrister

like his father, but because of his weakness in studies, he could not complete

his high-school education.lost his wife and son. Failure in life made him

a depressed alcoholic. He died because of a liver disease on June 18th,

1948 in a municipal hospital in Mumbai, known at the time as Bombay. |

|

|

Although

a Dewan, his father was a very generous person, and his income was spent

on helping the poor and the needy. The family lived reasonably well, but

there were no savings. When his father died, the family found itself in

financial difficulties. By then, the British had entrenched themselves

in India and controlled the affairs of the states making it difficult for

a person to inherit his father's job. In the old days in India, a son usually

took over when the father retired or died. The British, however, wanted

people who were "qualified" for the job, so none of the sons could become

Dewan of Porbandar after Karamchand's death.

The

family faced severe economic problems after Karamchand's death in 1885.

The brothers-Laxmidas and Karsandas-did not have jobs, and there was no

hope of any of them inheriting the title of Dewan. The older brothers learned

to write legal briefs and earned a little to sustain the large family.

None of them were educated beyond elementary school, so the burden of resurrecting

the family fortunes fell on Mohan. Although his mother and other family

elders could not contemplate his going abroad for further studies, the

advice of more liberal counselors was that Mohan must go to England and

study law. With the British entrenched in India, they were going to demand

academic qualifications for all jobs.

|

|

Reluctantly,

and after many promises, Mohan was allowed to go to England. He not only

studied law but came in close touch with many eminent philosophers and

thinkers and spent many hours a day in discussions. He was able to absorb

a great deal from them and it was this group which contained George Bernard

Shaw and others who one day asked Mohan to read with them the Bhagwad Gita

and explain it to them. Mohan was ashamed that he had never read the scripture

himself and did not know Sanskrit to be able to read the original. Instead,

he read with them Edwin Arnold's English translation of the Gita-The Song

Celestial-which revealed to him the richness of Hindu scriptures.

Mohan

was impressed not only by the reading of the Gita but by the "friendly"

study that this group of Englishmen were trying to make of other scriptures.

Mohan's motto in life, "A friendly study of all scriptures is the sacred

duty of every individual." was born in England during this educational

tour. He studied all the religions of the world and found there was a great

deal in each one of them for all of us to absorb in our own lives. His

respect for different religions and willingness to study them with an open

mind is what broadened his perspective and enriched his mind.

He

returned from England in 1891 very much a "brown sahib." He tried to introduce

his western habits in his traditional home in Porbandar and, indeed, spent

so much time and energy in this pursuit that he forgot that he had to set

up a legal practice and start earning to support the family. Weeks passed

and once again it was Kastur who opened his eyes to his responsibilities

when she gently chided him for his futile attempts to westernize the family

rather than earning money to support it.

|

|

For

someone as shy and timid as Mohan, setting up a legal practice was not

easy. He was not successful in Porbandar, so he went to Bombay and met

with no success there either. He tried to get a job as a school teacher

to teach English but was astounded to learn that he did not have the requisite

qualifications to teach English, only to practice law in English. After

struggling for several months, he decided to go back to Porbandar and do

what his brothers were doing- write legal briefs. His brothers were very

disappointed, especially since the family had taken enormous loans to send

Mohan to England to study. How would they repay the loans if Mohan was

going to end up writing briefs?

Laxmidas

had a Muslim friend, Dada Abdullah, who had gone to South Africa and made

a lot of money as a trader. He now had a legal case with another Muslim

trader which had been going on for a long time without resolution. Both

traders had white, English-speaking lawyers, and since neither of them

could speak English, communication was very poor. Dada Abdullah heard about

Mohan through his brother and invited Mohan to come to South Africa on

a one-year contract to work as an interpreter for him.

Mohan

once again left India in 1893 to go to another new part of the world to

try his luck. The urgency of finding a job and making money was impressed

upon him, and he was conscious of his responsibilities, but he was also

conscious of his "status" in life as an England-trained Barrister-at-Law.

Consequently, a week after his arrival, when it was time for Mohan to go

to Pretoria to attend the case in the Supreme Court, Mohan decided he must

travel by first class. Anything lower than that would be undignified. He

ordered his ticket by mail.

Mahatma

Gandhi Life with Photos, Pictures....... |

|

There

were so many coincidences in Mohan's life that seemed to nudge him towards

a transformation from a mere Mohan to Gandhiji. Had he not gone to England,

had he not been exposed to English intellectuals, had he not studied law,

had he not been a failure in India, had he become a school teacher, had

he not accepted the invitation to South Africa, had he not had that false

sense of dignity and, above all, and had South African whites not had aggravating

racial prejudices, we would not be writing or reading about Gandhi today.

It was the cumulative effect of all these and many other little coincidences

that conspired to give us the "Apostle of Peace".

The

transformative experience was when he encountered a white co-passenger

who boarded the train in Pietermaritzburg, who seeing a "black" Mohan sitting

in a first class compartment, reacted with a total lack of dignity. Mohan

was picked up and thrown off the train for refusing to vacate the first

class compartment. This humiliation, Gandhi wrote later, first caused him

to react in anger with a desire to respond violently. He saw the futility

of such action and rejected it. The next thought was to leave South Africa

and go back to India where he felt he could live in greater dignity and

honor but rejected that also because he felt that it was not appropriate

to run away from a problem. Besides, I feel that at the back of his mind

was the overriding question, "What will I tell my wife and family? That

I have failed once again?"

The

third thought, which occurred to him as the dawn was breaking over Pietermaritzburg

on that fateful day, was to seek justice through non-violent action. This

is the point at which "satyagraha" was born. He used it effectively in

South Africa for 22 years and won many concessions for his fellow Indians.

The government, however, reneged on these concessions after Mohan left

South Africa in 1915. There are those who wonder why Mohan did not fight

the cause of the African natives of South Africa. Some historians have

uncharitably labeled Gandhiji as a "racist", but I think they miss a very

important point.

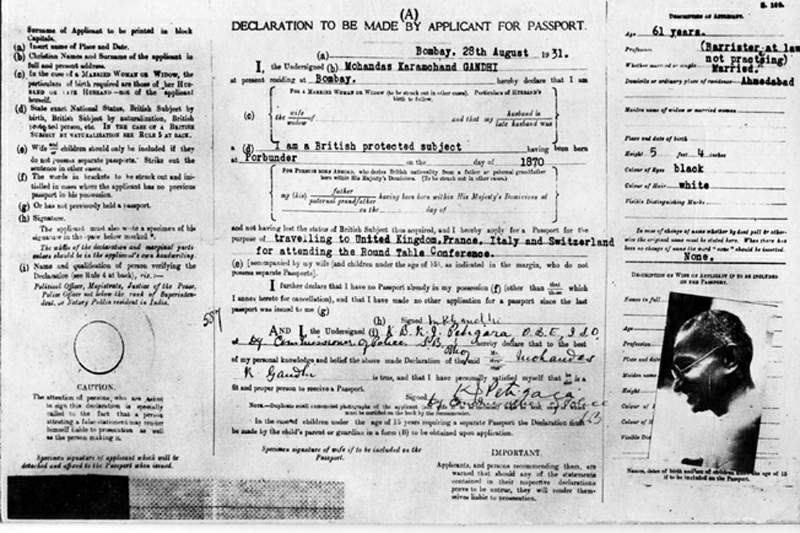

Gandhi's passport issued on August 28, 1931 for his travel to attend

Round Table Conference.

|

|

Gandhiji

was unfamiliar with South Africa and the conditions and the language of

the native Africans. He was also equally unfamiliar with the philosophy

of non-violence which was being evolved one campaign at a time. It was

hard enough for him to convince his own people about this philosophy without

having to translate it for the native Africans who were known for their

militancy.

Much

later, in 1939, when he was much wiser and more confident about his philosophy

of satyagraha, he told a delegation of African American leaders led by

Dr. Howard Thurman that he had to prove the success of his philosophy to

his own people in India before bringing it to the United States. This was

in response to Dr. Thurman's invitation to Gandhiji to lead the civil rights

movement in the United States.

If

he was so reluctant to enlarge the scope of his philosophy in 1939, how

could he consider getting the native Africans involved thirty years earlier?

I think it was more his sense of prudence than his prejudice that kept

him away from dealing with the native African problems. In 1906 he witnessed

the "Zulu War" closely as a Red Cross volunteer caring for the injured

and the dead, mostly Zulus. He writes about this experience with total

disgust. He had witnessed what was conventional war at the time and knew

that there were certain rules that the soldiers observed. In the Zulu war

he saw the British flouting all decency and decorum and massacring the

Zulus mercilessly. They were hunted down like animals and butchered by

the British. Until this event he was an admirer of western civilization.

Now a crack had been formed, and this widened into a gulf after his visit

to England in 1909 to plead the case of the Indians in South Africa. When

he found the British politicians dismissing everything he had to say with

contempt, he was filled with a total revulsion for western civilization

|

|

On

his journey back from London to Cape Town-about 15 days by ship--he was

overcome by a desire to write his first book "Hind Swaraj" formulating

a plan for independent India. The obsession was so great that he began

writing on the ship stationary with a pencil. The thoughts were coming

so furiously that he could not stop writing. When his right hand began

to ache, he switched to writing with his left. The book was completed before

he reached Cape Town and became distinguished for its anti-western civilization

message. He asked India to reject western civilization completely because

it had nothing worthwhile to offer. He entered a period of exclusivism.

In

1915, Gandhiji decided he would gain nothing for Indians outside India

as long as Indians within India remained subjects of British Imperialism.

They must be liberated first for Indians elsewhere to gain any respect

or equality. Thus, he decided to move to India and explore ways in which

he could participate in the freedom struggle.

He

entrusted his work in South Africa and the Phoenix Settlement Ashram that

he started in 1903 to the care of Mr. Albert West and Mr. Henry Polak,

two British friends who had worked with him closely in South Africa. The

whole family left South Africa in 1914 with Gandhiji, Kasturba and Hermann

Kallenbach, and another Jewish South African friend going to England and

the rest of the family sailing for India. Gandhiji wanted to help with

the war effort in England, but soon after his arrival, he was struck by

pneumonia and almost bed-ridden. For a while Kasturba nursed him and participated

in sewing uniforms for English soldiers, but when the doctors realized

the British winter was not going to help Gandhiji overcome his ailment,

they suggested he leave for India

|

|

Kallenbach

wanted to accompany them to India, but as a German Jew he was not given

a visa by the British and so he had to return to South Africa. Gandhiji

and Kasturba arrived in India and were given a welcome they had not anticipated.

Gandhiji was not aware that his reputation had preceded him. He became

a national leader on arrival. Gopalkrishna Gokhale, Gandhiji's political

mentor in India, advised Gandhiji to spend a year traveling around India

learning about the problems and making contact with the people. After his

travels, he started an ashram at Bochraj in Gujarat and later was induced

to visit Champaran in Bihar. The emissary of the poor and exploited peasants

of Champaran was so persistent that Gandhiji could not refuse him. When

Gandhiji went there and saw the conditions, he was shocked beyond belief

and launched a legal campaign that forced the British farmers to abandon

their exploitation and give relief to the peasants. It was his first significant

and major victory in India achieved through non-violence. This incidence

catapulted Gandhiji to the national scene.

In

1919 he launched a national campaign against the Rowlatt Act which was

designed by the British to oppress and suppress the Indians and their desire

for independence. The movement generated some violence in parts of the

country, especially in the north. In Punjab some misguided youth attacked

a British school teacher and pushed her around. The British government

appointed General Dyer as the military governor of the State of Punjab

with the authority to ruthlessly curb all defiance of authority. He imposed

martial law, prohibiting the assembly of more than five people and suspending

all civil liberties in the state.

|

|

On

April 13, 1919, more than ten thousand men, women and children assembled

in the Jallianwala bagh in the heart of the city of Amritsar to non-violently

protest against the martial law. General Dyer was unwilling to tolerate

such an act of defiance. He brought in his troops, blocked off the only

exit from the walled ground and ordered the troops to shoot into the crowd.

Within an hour 386 men, women and children lay dead and 1605 were critically

injured. These were the British figures of casualties while the India figures

are very different. The Indians place the number of dead beyond 1,000.

However, General Dyer followed with more draconian laws like commanding

all Indians to crawl on their bellies when passing the street where the

English school teacher was assaulted. Anyone who refused would be flogged

to death. He also ordered that the injured in the firing should not be

attended to by anyone for the next 72 hours, even if they died. This incident

raised so much anger in India that a violent revolution could very easily

have resulted, but Gandhiji stepped in to calm the people. He said we can

not be to the British as they have been to us. It will not make us any

different from them. The civilized thing to do is not to ever stoop down

to the level of the oppressor, but to try at all times to raise the oppressors

to new heights of awareness. This is the point at which Gandhiji reverted

back to inclusivity. He urged Indians to remember that we must not only

liberate ourselves politically but also liberate ourselves spiritually.

Swaraj, he said, is not just external freedom; it is also internal freedom.

Aldous Huxley, the eminent British historian, is perhaps the only one who

has recognized the fact that in liberating India non-violently, Gandhiji

also liberated the British from their own imperialism. In other words,

the non-violent campaign in India elevated the British to a new awareness

of themselves.

|

|

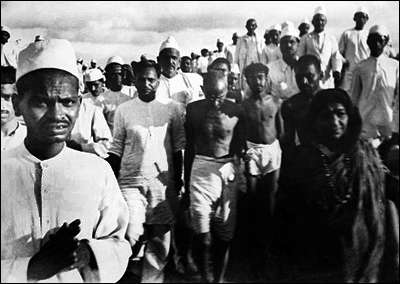

However,

after the 1919 campaign, the next major campaign was the Salt March in

1930. There were many smaller campaigns in between. The Salt March once

again focused the attention of the world on India's struggle for freedom.

Instead of arousing derision or indifference as most violent freedom struggles

around the world do, the Indian struggle evoked world sympathy. Suffering

has a tendency to do that. The British were lacksadasical about this campaign.

They did not think that the defiance of the tax on salt would arouse such

emotions all over India and the world. They were not prepared for the consequences.

The whole nation stood up in defiance of the British, and as some historians

put it, another nail was hammered into the British coffin. Again what followed

was smaller campaigns at regional levels until 1942, when the Congress

passed the "Quit India" resolution. This campaign again roused national

consciousness and the jails were filled to the brim. Gandhiji and his party

were imprisoned in Aga Khan Palace near Pune. It was not a palace in the

accepted sense, and only a part of it was cordoned off and used as a jail.

Kasturba died in prison in 1944. This was a great blow for Gandhiji.

Throughout

his campaign for freedom, Gandhiji was concerned about the divisions in

India which were exacerbated by the British who followed the "Divide and

Rule" policy. There was the serious division between Hindus and Muslims

and within the Hindus between the various castes. Short of leading a major

revolution to bring about unity, Gandhiji did everything he could to break

down the barriers and build bridges. He realized that political freedom

from the British would be meaningless so long as we hated each other and

were willing to kill because of our prejudices. Through fasts, through

education, through example, through preaching he tried his best to teach

the people to respect and appreciate each other

|

|

In

1935, Gandhiji realized the Indian National Congress had no intentions

of pursuing his policy of non-violence after independence. He resigned

his membership. The Congress, however, was unwilling to let go of his leadership

of the freedom struggle. In the forties when independence became a possibility,

the British opposed partition of the country to create Pakistan. Gandhiji

was against this, but the Congress was inclined to accept it. When Gandhiji

proposed allowing the Muslim League to form the interim government to placate

its fears of Hindu domination, the Congress Party leadership threatened

a civil war.

The

Congress leadership claimed the people would not accept this plan and there

would be civil war. The question is were the leaders right in presuming

how the people would react or could they have supported Gandhi in explaining

to the people the wisdom of remaining one country and giving the plan a

fair opportunity to prove its efficacy? There is the underlying feeling

that the leadership was not willing to accept the plan so why take it to

the people at all. At this point Gandhi gave up discussing the partition

of the country and left it to the leaders and the British to do what they

felt was right. The rest is history. The country was partitioned; there

was a civil war which left both countries with a legacy of hate that will

take centuries to heal. Was the price worth it? Could we have paid the

same price for a unified country? Would the long-term results have been

different? These are questions that can not be answered.

|

|

Bapu

lost his desire to live. Until this point whenever anyone asked him how

long he would like to live, he would say with a smile: I would like to

live for 125 years because there is so much I need to accomplish. He had

a zest for life and a mission that he wanted to see fulfilled. By 1946,

this came to a sad end and he began speaking of death. Yet, he never showed

outwardly the despondency that he must have felt within. He still continued

to work, and he continued to guide people in their work for social and

economic resurgence of India. He even went to Noakhali in Bengal that became

East Pakistan, where rioting was at its worst on the eve of partition.

Hindus and Muslims were literally butchering each other and some of the

worst acts of inhumanity took place in this area. He went with a handful

of helpers and brought about peace and sanity in the area. An accomplishment

that was recognized by Lord Mountbatten when he wrote his biography was

that Gandhi brought peace all by himself in East Pakistan while the Indian

Army had to kill and crush many thousands in West Pakistan before peace

was accomplished.

The

assassination of Gandhiji was ironically engineered by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak

Sangh (RSS) because it felt Gandhiji had agreed to the creation of Pakistan.

It had made an avowed and ambitious program to reunite its country. Yet,

had it not been for its militancy during the 1946/47 negotiations, India

may have been one country. The RSS is to shoulder the entire blame for

creating an atmosphere of violence and revenge in the country that made

it impossible for sanity to prevail.

|

|

Having

accepted partition, the Congress leadership tacitly accepted the consequences

of partition. The bloodshed, the loss of lives and property on both sides

were to be expected. No one was going to be uprooted from places where

he/she had lived for generations with a smile and move to another place.

For the Congress leadership to then succumb to militant Hindu demand that

the cash assets due to Pakistan be confiscated to compensate the Hindus

who lost their lives and property was unethical to say the least. They

were playing populist politics without considering the long term consequences

of their action. Gandhiji said if my country is to embark on its new and

independent life on a blatantly immoral act then I would prefer death.

He fasted and forced the government to release the money to Pakistan. Had

the government kept the money as the RSS demanded, there would have been

a worse civil war than the country had witnessed and India would have had

no moral grounds to stand on when the international community judged the

situation. We had lost our senses then but had we held onto the money,

we would have lost our souls also.

Within

the country, in the bureaucracy and in the government, there was not much

enthusiasm for Gandhiji's life. Secretly, everyone was interested in making

him a martyr. A martyred Gandhi was more beneficial to the rulers than

a living Gandhi. The bureaucracy had already experienced and enjoyed a

princely lifestyle under the British which they were unwilling to give

up. The politicians were eager to be participants in such a life. Gandhiji

opposed this wholeheartedly, and had he lived long enough, he would most

certainly have pressured the government to adopt a more simple lifestyle.

He often said the government of independent India must reflect the poverty

of the nation. The politicians and the bureaucrats, on the other hand,

were eager to replace the British and maintain the oppressive and opulent

structure created by the British.

Gandhi

ji was assasinated on January 30, 1948 at Delhi, India.

Mahatma

Gandhi Life with Photos, Pictures

|

Welcome

to

Rajesh

Chopra's

Guest

Book

and

comments Please

|